by Gurujot Singh Khalsa, Espanola NM

Fall 2010

Originally published on SikhNet.com

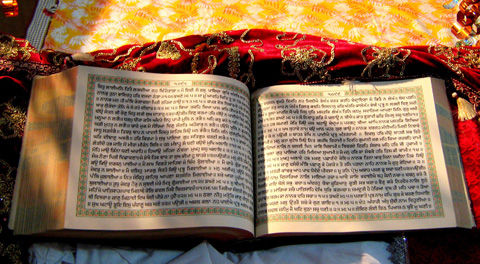

The act of translation contains its own intrinsic impossibility. That is, every translation is only an approximation of the original. That does not mean that we should not attempt the impossible! In fact, I believe it’s actually necessary to do so.

I find it somewhat difficult to translate Gurbani into English because one word in Gurbani could require a whole story or several paragraphs of explanation to understand the whole meaning. Many of the examples used in Gurbani require an understanding of the culture that existed at the time it was written.

Gurbani was written over 300 years ago, on the other side of the planet from me. For example, many existing Hindu traditions and Vedic stories are mentioned, but if you are not familiar with those stories and traditions the comparisons lose their meaning.

Completing the Meaning

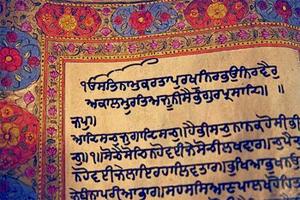

When reading in Gurmukhi, the words seem to be deeper, more significant, and more powerful. I think one reason is that Gurbani forces your mind to complete the meaning. Let’s take this line for example, “Safal darshan pekhat puneet.” Dr. Sant Singh translated it as “Blessed is His Darshan; receiving it, one is purified.”

safal – successful, fruitful

darshan – vision, blessing

pekhat – seeing

puneet – pure, holy

So if we break this line down in Gurmukhi there is a two-word subject “safal darshan” – ‘fruitful vision’, and a two-word predicate “pekhat puneet” – ‘seeing and becoming pure’. I have inserted the word ‘becoming’ because that’s how it makes sense to me.

So if we break this line down in Gurmukhi there is a two-word subject “safal darshan” – ‘fruitful vision’, and a two-word predicate “pekhat puneet” – ‘seeing and becoming pure’. I have inserted the word ‘becoming’ because that’s how it makes sense to me.

So, already we find that taking it in its purest simple form, the line doesn’t make sense in English and we have to start adding words and interpretations. It wouldn’t make sense if the line just said, “fruitful vision, seeing pure” even though it’s literal to the poetic power and simplicity of the Gurmukhi. There is no “His” “receiving it” “one” “is.” It’s pure and esoteric.

In Gurmukhi form, this line leads you through a process. It doesn’t say everything, but it lets you discover the meaning within the line. Your mind gets to interject who is doing the seeing, and who has the fruitful vision.

Your mind decides if the fruitful vision is causing the purity. Based on your perception your mind interprets the experience the Guru is describing. The point is that the pure Gurmukhi is interactive in its simplicity. That’s the beauty of Gurbani: it is a transcendental conversation with your soul and instruction to your mind.

The Trouble with Tenses

I have also noticed that translations tend to add tenses that aren’t there in Gurmukhi. “…my sleeping mind has been awakened” (..so-eyo man jageyo) Directly translating it, it would be “sleeping mind, awaken(ed/ing).” We are adding the past tense to make it make sense by saying “has been.” But how do we know that this line is telling us a story in the past? The Gurmukhi doesn’t mention “my” singular, nor is it in past tense. What if we said, “…the sleeping mind is awakened.”

Or what if this line is a command? “”…awaken your sleeping mind.” There are other lines of Gurbani translated in future tense such as, “The doubts of your mind will be dispelled.” (…man ki laahe bharaant) Instead, I think it could be “The doubts of the mind are dispelled.”

… the Shabd is transcendent and the Gurbani describes experiences that are actually outside of time and space. Everything is in the moment and everything is happening now – in the moment the word is spoken.

Gurbani speaks to the collective human mind (not the singular “I”). The Siri Guru Granth Sahib is our living Guru so it is ever-present and always true in every moment, so whenever I can, I lean towards using a present continuous tense, and unless absolutely necessary I do not use the past or future tense.

Restoring Poetic Power

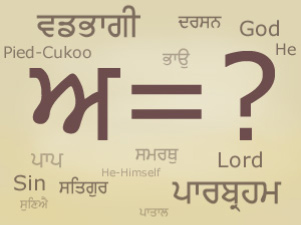

Gurbani gives the feeling of the Creator as an all-pervading Presence but we tend to translate it in such a way that it seems like a personality. Even though the Creator is beyond personality, we are always referring to a “Him.”

Gurbani gives the feeling of the Creator as an all-pervading Presence but we tend to translate it in such a way that it seems like a personality. Even though the Creator is beyond personality, we are always referring to a “Him.”

Even using the word “God” is limiting. Instead of saying “God” we can say “The Divine” or “The Infinite.” To me, that takes God from a noun to an adjective, which fits better because everything is God. So to use a word that makes God a personality is misleading, but to make it an attribute that can be applied to any noun (everything) does more justice to the idea.

It does seem like I’m getting very nitty-gritty with words here, when words are just symbols. Words just represent ideas, and the current translations do fairly well at conveying the ideas in Gurbani to modern English vernacular. So what’s the big deal if we change it from “I” to “the human,” if we take it out of past tense “have been saved” to “be saved?”

Well, it is because the Gurus and other writers of the Siri Guru Granth Sahib chose their words very carefully. Bani is sacred sound. Reading Gurbani takes you through a transformation.

Gurbani is subtle, powerful, and always evolving as your own concepts evolve. So anything we can do to restore the poetic power, the literal meaning and pure simplicity of it is not only good, but it is necessary.

Please help with the Gurmukhi to English dictionary project. We want to restore the deeper meanings to the words of the Guru. This article is not intended to criticize any existing translation of the Siri Guru Granth Sahib. I am not a scholar, so this is only an exploration of ideas.

About the Author

Gurujot Singh Khalsa serves as Creative Director for SikhNet. He was born and raised a Sikh in New Mexico, USA. In eighth grade, he started going to school in Amritsar, India and became inspired to learn more about Sikhi. Under the disciplined environment there, he learned about Sikhi, Kundalini Yoga, Gatka, Gurmukhi, Punjabi, Raag Kirtan, etc. and had the opportunity to have darshan and do seva at Sri Harimandir Sahib. He plays the Dilruba, an instrument that was either played by/invented by/ promoted by Guru Gobind Singh.

Gurujot Singh Khalsa serves as Creative Director for SikhNet. He was born and raised a Sikh in New Mexico, USA. In eighth grade, he started going to school in Amritsar, India and became inspired to learn more about Sikhi. Under the disciplined environment there, he learned about Sikhi, Kundalini Yoga, Gatka, Gurmukhi, Punjabi, Raag Kirtan, etc. and had the opportunity to have darshan and do seva at Sri Harimandir Sahib. He plays the Dilruba, an instrument that was either played by/invented by/ promoted by Guru Gobind Singh.